PM says: “The challenge is our history of executing post-mvp. We get things out the door and jump onto the next train, then abandon them.”

UX says: “We haven’t found the sweet spot between innovation speed & quality, at least in my 5 years.”

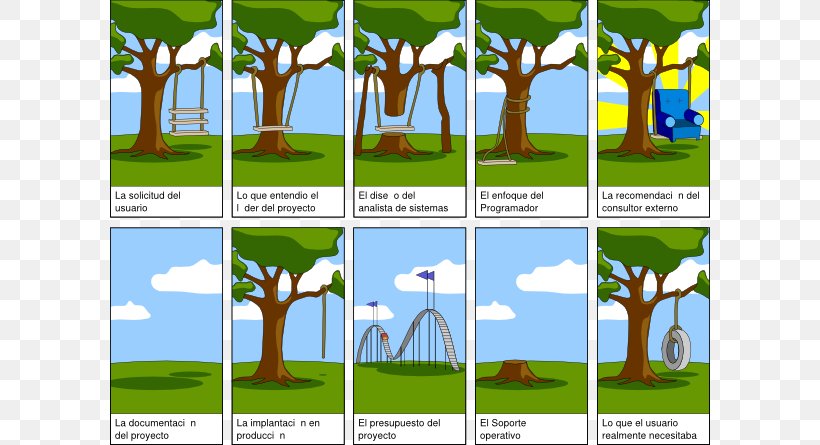

Customer says: “What’s taking so long? I asked you for 44 features two years ago, and you haven’t given me any of the ones I really wanted.”

Sound familiar? I’m sure you’ve heard variations on these themes – hell, I’ve heard these themes in every tech firm I’ve worked.

One of the most humbling lessons I keep learning: nothing is ever truly “complete”, but if you’re lucky some features and products get shipped.

I used to think this was just a moral failing of the people or the culture, and that there *had* to be a way this could get solved. Why can’t we just figure this shit out? Aren’t there any leaders and teams that get this right?

It’s Better for Creatives, Innit?

I’m a comics reader, and I like to peer behind the curtain and learn about the way that creators succeed. How do amazing writers and artists manage to ship fun, gorgeous comics month after month?

Some of the creators I’ve paid close attention to, say the same thing as even the most successful film & atV professionals, theatre & clown types, painters, potters and anyone creating discrete things for a living:

Without a deadline, lots of great ideas never quite get “finished”. And with a deadline, stuff (usually) gets launched, but it’s never really “done”. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Worst of both worlds.

In commercial comics, the deal is: we ship monthly, and if you want a successful book, you gotta get the comic to print every month on schedule. Get on the train when it leaves, and you’re shipping a hopefully-successful comic. And getting that book to print means having to let go even if there’s more you could do: more edits to revise the words, more perfect lines, better colouring, more detailed covers.

Doesn’t matter. Ship it or we don’t make the print cutoff. Get it out, move on to the next one.

Put the brush down, let the canvas dry. Hang up the painting.

No Good PM Goes Unpunished

I think about that a lot. Could I take another six months, talk to more research subjects, rethink the UX flow, wait til that related initiative gets a little more fleshed out, re-open the debate about the naming, work over the GTM materials again?

Absolutely!

And it always feels like the “right” answer – get it finished for real, don’t let it drop at 80%, pay better attention to the customers’ first impressions, get the launch materials just right.

And if there were no other problems to solve, no other needs to address, we’d be tempted to give it one more once-over.

But.

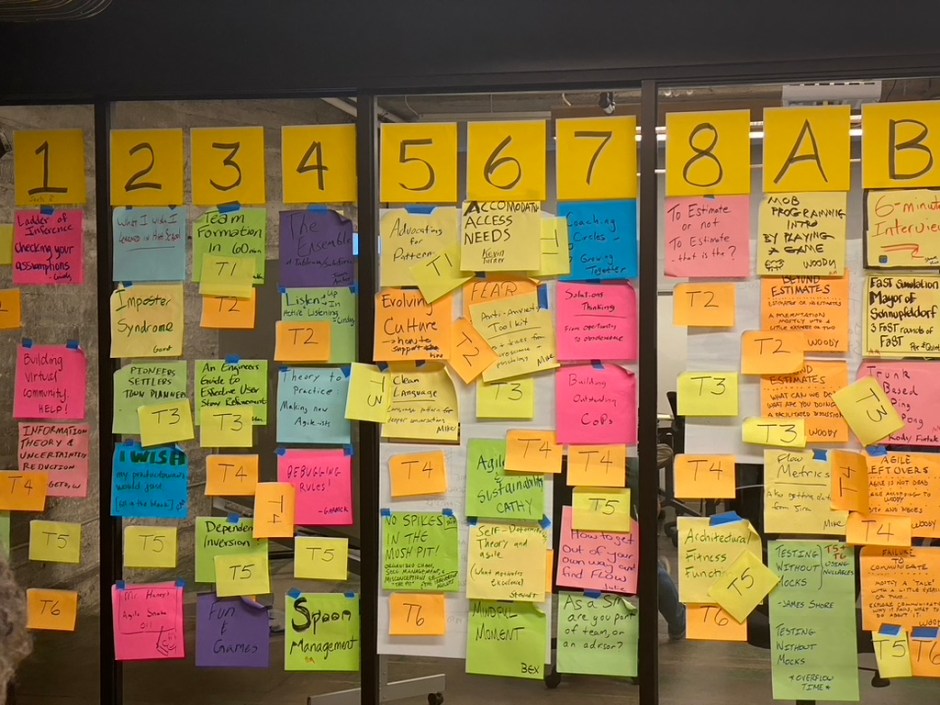

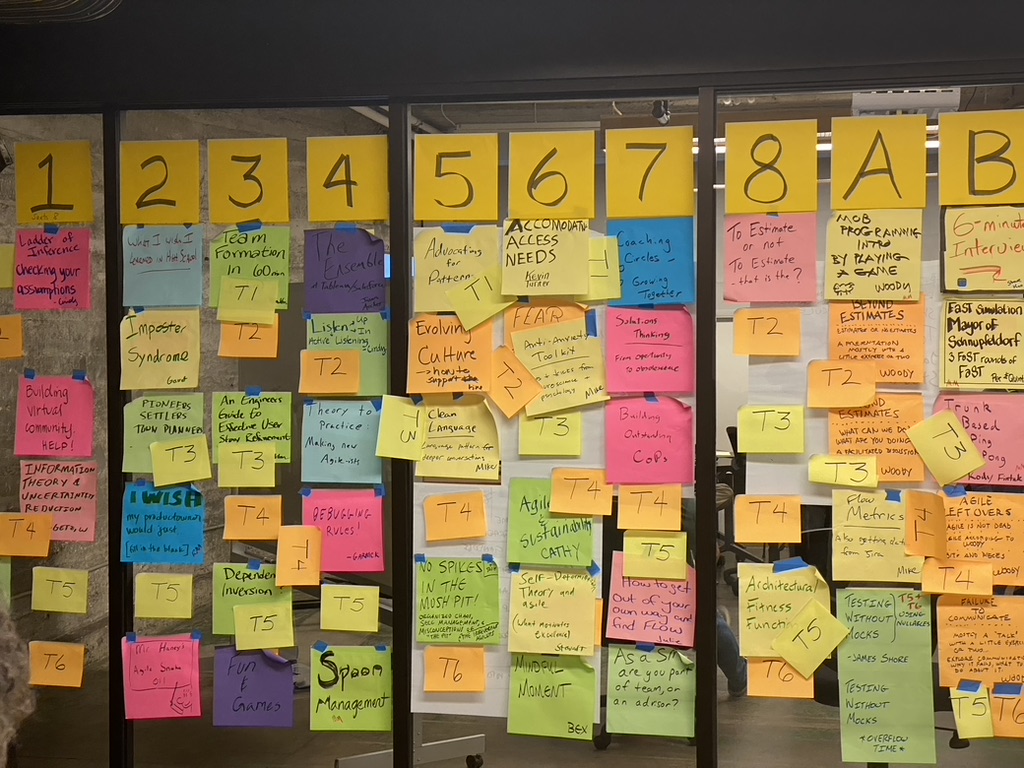

There’s a million things in the backlog.

Another hundred support cases that demand a real fix to another even more problematic part of the code.

Another rotting architecture that desperately needs a refactor after six years of divergent evolution from its original intent.

Another competitive threat that’s eating into our win-loss rate with new customers.

We don’t have time to perfect the last thing, cause there’s a dozen even-more-pressing issues we should turn our attention to. (Including that one feature that really *did* miss a key use case, but also another ten features that are getting the job done, winning over customers, making users’ lives better EVEN IN THEIR IMPERFECT STATE.)

Regrats I’ve Had a Few

I regret a few decisions I wish I’d spent more time perseverating on. There’s one field name that still bugs me every time I type it in, a workflow I wish I’d fought harder to make more intuitive, and an analytic output that I wish we’d stuck to our guns in reporting it as it comes out of the OS.

But I *more* regret the hesitations that have kept me from moving on, cutting bait, and getting 100% committed to the top three problems that I’m too often saying “Those are key priorities that are top of the list, we should get that kicked off shortly.” And then somehow let slip til next quarter, or end up six months later than a rational actor would have addressed.

What is it he said? “Let’s decide on this today as if we had just been fired, and now we’re the cleanup crew who stepped in to figure out what those last clowns couldn’t get past.”

Lesson I Learned At Microsoft

Folks used to say “always wait for version 3.0 for new Microsoft products” (back in the packaged binaries days – hah). And I bought into it. Years later I learned what was going on: Microsoft deliberately shipped v1.0 to gauge any market interest (and sometimes abandoned there), 2.0 to start refining the experience, and getting things mostly “right” and ready for mass adoption by 3.0.

If they’d waited to ship until they’d complete the 3.0 scope, they’d have way overinvested in some market dead-ends and built features that weren’t actually crucial to customers’ success and not had an opportunity to listen to how folks responded to the actual (incomplete, hardly perfect) product in situ.

What Was The Point Again?

Finding the sweet spot between speed and quality strikes me as trying to beat the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle: the more you refine your understanding of position, the less sure you are about momentum. It’s not that you’re not trying hard to get both right: I have a feeling that trying to find the perfect balance is asymptotically unachievable, in part because that balance point (fulcrum) is a shifting target: market/competition forces change, we build better core competencies and age out others, we get distracted by shinies and we endure externalities that perturb rational decision-making.

We will always strive to optimize, and that we don’t ever quite get it right is not an individual failure but a consequence of Dunbar’s number, imperfect information flows, local-vs-global optimization tensions, and incredible complexity that will always challenge our desire to know “the right answer”. (Well, it’s “42” – but then the immediate next problem is figuring out the question.)

We’re awesome and fallible all at the same time – resolving such dualities is considered enlightenment, and I envy those who’ve gotten there. Keep striving.

(TL;DR don’t freak out if you don’t get it “right” this year. You’re likely to spend a lot of time in Cynefin “complex” and “chaos” domains for a while, and it’s OK that it won’t be clear what “right” is. Probe/Act-Sense-Respond is an entirely valid approach when it’s hard-to-impossible to predict the “right” answer ahead of time.)