I was asked recently what I do to ensure my team knows what success looks like. I generally start with a clear definition of done, then factor usage and satisfaction into my evaluation of success-via-customers.

Evaluation Schema

Having a clear idea of what “done” looks like means having crisp answers to questions like:

- Who am I building for?

- Building for “everyone” usually means it doesn’t work well for anyone

- What problem is it fixing for them?

- I normally evaluate problems-to-solve based on the new actions or decisions the user can take *with* the solution that they can’t take *without* it

- Does this deliver more business value than other work we’re considering?

- Delivering value we can believe in is great, and obviously we ought to have a sense that this has higher value than the competing items on our backlog

What About The Rest?

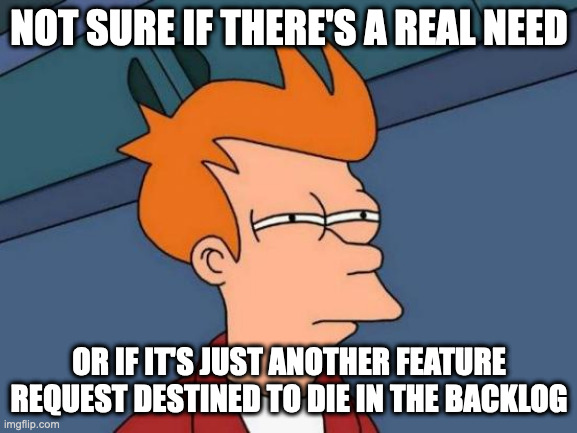

My backlog of “ideas” is a place where I often leave things to bake. Until I have a clear picture in my mind who will benefit from this (and just as importantly, who will not), and until I can articulate how this makes the user’s life measurably better, I won’t pull an idea into the near-term roadmap let alone start breaking it down for iteration prioritization.

In my experience there are lots of great ideas people have that they’ll bring to whoever they believe is the authority for “getting shit into the product”. Engineers, sales, customers – all have ideas they think should get done. One time my Principal Engineer spent an hour talking me through a hyper-normalized data model enhancement for my product. Another time, I heard loudly from many customers that they wanted us to support their use of MongoDB with a specific development platform.

I thanked them for their feedback, and I earnestly spent time thinking about the implications – how do I know there’s a clear value prop for this work?

- Is there one specific user role/usage model that this obviously supports?

- Would it make users’ lives demonstrably better in accomplishing their business goals & workflows with the product as they currently use it?

- Would the engineering effort support/complement other changes that we were planning to make?

- Was this a dealbreaker for any user/customer, and not merely an annoyance or a “that’s something we *should* do”?

- Is this something that addresses a gap/need right now – not just “good engineering that should become useful in the future”? (There’s lots of cool things that would be fun to work on – one time I sat through a day-long engineering wish list session – but we’re lucky if we can carve out a minor portion of the team’s capacity away from the things that will help right now.)

If I don’t get at least a flash of sweat and “heat” that this is worth pursuing (I didn’t with the examples mentioned), then these things go on the backlog and they wait. Usually the important items will come back up, again and again. (Sometimes the unimportant things too.) When they resurface, I test them against product strategy, currently-prioritized (and sized) roadmap and our prioritization scoring model, and I look for evidence that shows me this new idea beats something we’re already planning on doing.

If I have a strong impression that I can say “yes” to some or all of these, then it also usually comes along with a number of assumptions I’m willing to test, and effort I’m willing to put in to articulate the results this needs to deliver [usually in a phased approach].

Delivery

At that point we switch into execution and refinement mode – while we’ve already had some roughing-out discussions with engineering and design, this is where backlog grooming hammers out the questions and unknowns that bring us to a state where (a) the delivery team is confident what they’re meant to create and (b) estimates fall within a narrow range of guesses [i.e. we’re not hearing “could take a day, could take a week” – that’s a code smell].

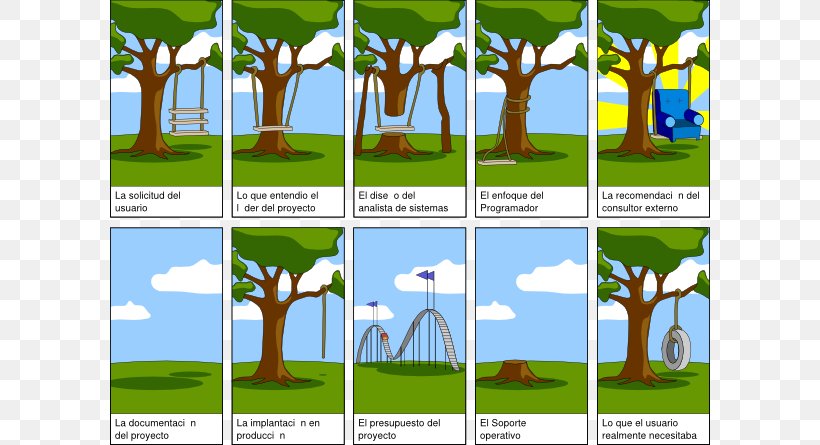

Along the way I’m always emphasizing what result the user wants to see – because shit happens, surprises arise, priorities shift, the delivery team needs a solid defender of the result we’re going to deliver for the customer. That doesn’t mean don’t flex on the details, or don’t change priorities as market conditions change, but it does mean providing a consistent voice that shines through the clutter and confusion of all the details, questions and opinions that inevitably arise as the feature/enhancement/story gets closer to delivery.

It also means making sure that your “voice of the customer” is actually informed by the customer, so as you’re developing definition of Done, mockups, prototypes and alpha/beta versions, I’ve made a point of taking the opportunity where it exists to pull in a customer or three for a usability test, or a customer proxy (TSE, consultant, success advocate) to give me their feedback, reaction and thinking in response to whatever deliverables we have available.

The most important part of putting in this effort to listen, though, is learning and adapting to the feedback. It doesn’t mean rip-sawing in response to any contrary input, but it does mean absorbing it and making sure you’re not being pig-headed about the up-front ideas you generated that are more than likely wrong in small or big ways. One of my colleagues has articulated this as Presumptive Design, whereby your up-front presumptions are going to be wrong, and the best thing you can do is to put those ideas in front of customers, users, proxies as fast and frequently as possible to find out how wrong you are.

Evaluating Success

Up front and along the way, I develop a sense of what success will look like when it’s out there, and that usually takes the form of quantity and quality – useage of the feature, and satisfaction with the feature. Getting instrumentation of the feature in place is a brilliant but low-fidelity way of understanding whether it was deemed useful – if numbers and ratios are high in the first week and then steadily drop off the longer folks use it, that’s a signal to investigate more deeply. The user satisfaction side – post-hoc surveys, customer calls – to get a sense of NPS-like confidence and “recommendability” are higher-fidelity means of validating how it’s actually impacting real humans.