Ever since Microsoft announced the “Bash on Windows” inclusion in the Anniversary update of Win10, I’ve been positively *itching* to try it out. I spent *hours* in Git Bash, Cygwin and other workarounds inside Windows to get tools like Vagrant to work natively in Windows.

Spoiler: it never quite worked. [Aside: if anyone has any idea how to get rsync to work in Cygwin or similarly *without* the Bash shell on Windows, let’s talk. That was the killer flaw.]

Deciphering the (hidden) installation of Bash

I downloaded the update first thing this morning and got it installed, turned on Developer Mode, then…got stumped by Hanselman’s article (above) on how exactly to get the shell/subsystem itself installed. [Seems like something got mangled in translation, since “…and adding the Feature, run you bash and are prompted to get Ubuntu on Windows from Canonical via the Windows Store…” doesn’t make any grammatical sense, and searching the Windows Store for “ubuntu”, “bash” or “canonical” didn’t turn up anything useful.]

The Windows10 subreddit’s megathread today left incomplete instructions, and a rumour that this was only available on Win10 Pro (not Home).

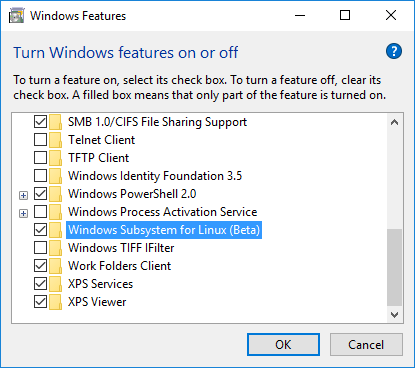

Instead, it turns out that you have to navigate to legacy control panel to enable, after you’ve turned on Developer Mode (thanks MSDN Blogs):

Control Panel >> Programs >> Turn Windows features on or off, then check “Windows Subsystem for Linux (Beta)”. Then reboot once again.

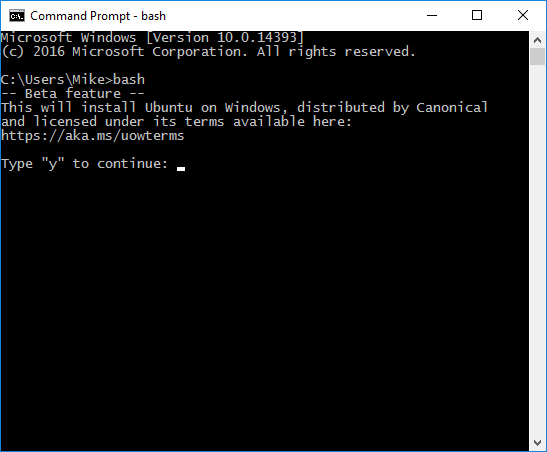

Then fire up CMD.EXE and type “bash” to initiate the installation of “Ubuntu on Windows”:

Now to use it!

Once installed, it’s got plenty of helpful hints built in (or else Ubuntu has gotten even easier than I remember), such as:

Npm, rpm, vagrant, git, ansible, virtualbox are similarly ‘hinted’.

Getting up-to-date software installed

Weirdly, Ansible 1.5.4 was installed, not from the 2.x version. What gives? OK, time to chase a rat through a rathole…

This article implies I could try to get a trusty-backport of ansible:

https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/commandline/2016/04/06/bash-on-ubuntu-on-windows-download-now-3/

Does that mean the Ubuntu on Windows is effectively an old version of Ubuntu? How can I even figure that out?

Running ‘apt-get –version’ indicates we have apt 1.0.1ubuntu2 for amb64 compiled on Jan 12 2016. That seems relatively recent…

Running ‘apt-cache policy ansible’ gives me the following output:

mike@MIKE-WIN10-SSD:/etc/apt$ apt-cache policy ansible ansible: Installed: 1.5.4+dfsg-1 Candidate: 1.5.4+dfsg-1 Version table: *** 1.5.4+dfsg-1 0 500 http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu/ trusty/universe amd64 Packages 100 /var/lib/dpkg/status

Looking at /etc/apt/sources.list, there’s only three listed by default:

mike@MIKE-WIN10-SSD:/etc/apt$ cat sources.list deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu trusty main restricted universe multiverse deb http://archive.ubuntu.com/ubuntu trusty-updates main restricted universe multiverse deb http://security.ubuntu.com/ubuntu trusty-security main restricted universe multiverse

So is there some reason why Ubuntu-on-Windows’ package manager (apt) doesn’t even list > 1.5.4 as an available installation? ‘Cause I was previously running v2.2.0 of Ansible on native Ubuntu (just last month).

I *could* run from source in a subdirectory from my home directory – but I’m shamefully (blissfully?) unaware of the implications – are there common configuration files that might stomp on each other? Is there common code stuffed in some dark location that is better left alone?

Or should I add the source repo mentioned here? That seems the safest option, because then apt should manage the dependencies and not leave me with two installs of ansible (1.5.4 and 2.x).

Turns out the “Latest Releases via Apt (Ubuntu)” seems to have done well enough – now ‘ansible –version’ returns “ansible 2.1.1.0”, which appears to be latest according to https://launchpad.net/~ansible/+archive/ubuntu/ansible.

Deciphering hands-on install dependencies

Next I tried installing vagrant, which went OK, but then complained about an incomplete installation:

mike@MIKE-WIN10-SSD:/mnt/c/Users/Mike/VirtualBox VMs/BaseDebianServer$ vagrant up

VirtualBox is complaining that the installation is incomplete. Please run

`VBoxManage --version` to see the error message which should contain

instructions on how to fix this error. mike@MIKE-WIN10-SSD:/mnt/c/Users/Mike/VirtualBox VMs/BaseDebianServer$ VBoxManage --version WARNING: The character device /dev/vboxdrv does not exist. Please install the virtualbox-dkms package and the appropriate headers, most likely linux-headers-3.4.0+. You will not be able to start VMs until this problem is fixed.

So, tried ‘sudo apt-get install linux-headers-3.4.0’ and it couldn’t find a match. Tried ‘apt-cache search linux-headers’ and it came back with a wide array of options – 3.13, 3.16, 3.19, 4.2, 4.4 (many subversions and variants available).

Stopped me dead in my tracks – which one would be appropriate to the Ubuntu that ships as “Ubuntu for Windows” in the Win10 Anniversary Update? Not that header files *should* interact with the operations of the OS, but on the off-chance that there’s some unexpected interaction, I’d rather be a little methodical than have to figure out how to wipe and reinstall.

Figuring out what is the equivalent “version of Ubuntu” that ships with this subsystem isn’t trivial:

- According to /etc/issue, it’s “Ubuntu 14.04.4 LTS”.

- What version of the Linux kernel comes with 14.04.4?

- According to ‘uname -r’, it’s “3.4.0+”, which seems suspiciously under-specific.

- According to /proc/version, its “Linux version 3.4.0-Microsoft (Microsoft@Microsoft.com) (gcc version 4.7 (GCC) ) #1 SMP PREEMPT Wed Dec 31 14:42:53 PST 2014”.

That’s enough for one day – custom versions of the OS should make one ponder. Tune in next time to see what kind of destruction I can wring out of my freshly-unix-ized Windows box.

P.S. Note to self: it’s cool to get an environment running; it’s even better for it to stay up to date. This dude did a great job of documenting his process for keeping all the packages current.