You’re one of a team of PMs, constantly firehosed by customer feedback (the terribly-named “feature request”**) and you even have a system to stuff that feedback into so you don’t lose it, can cross-reference it to similar patterns and are ready to start pulling out a PRD from the gems of problems that strike the Desirability, Feasibility and Viability triad.

And then you got pulled into a bunch of customer escalations (whose notes you intend to transform into the River of Feedback system), haven’t checked in on the backlog of feedback for a few weeks (I’m gonna have to wait til I’ve got a free afternoon to really dig in again), and I forget if I’ve updated that delayed PRD with the latest competitive insights from those customer-volunteered win/loss feedback.

Suddenly you realise your curation efforts – constantly transforming free-form inputs into well-synthesised insights – are falling behind what your peers *must* be doing better than you.

You suck at this.

Don’t feel bad. We all suck at this.

Why? Curation is rewarding and ABSOLUTELY necessary, but that’s doesn’t mean it isn’t hard:

- it never ends (until your products are well past time to retire)

- It’s yet one more proactive, put-off-able interruption in a sea of reactive demands

- It’s filled with way more noise than signal (“Executive reporting is a must-have for us”)

- You can bucket hundreds of ideas in dozens of classification systems (you ever tried card-sorting navigation menus with independent groups of end users, only to realise that they *all* have an almost-right answer that never quite lines up with the others?), and it’s oh-so-tempting to throw every vaguely-related idea into the upcoming feature bucket (cause maybe those customers will be satisfied enough to stop bugging you even though you didn’t address their core operational problem)

What can you do?

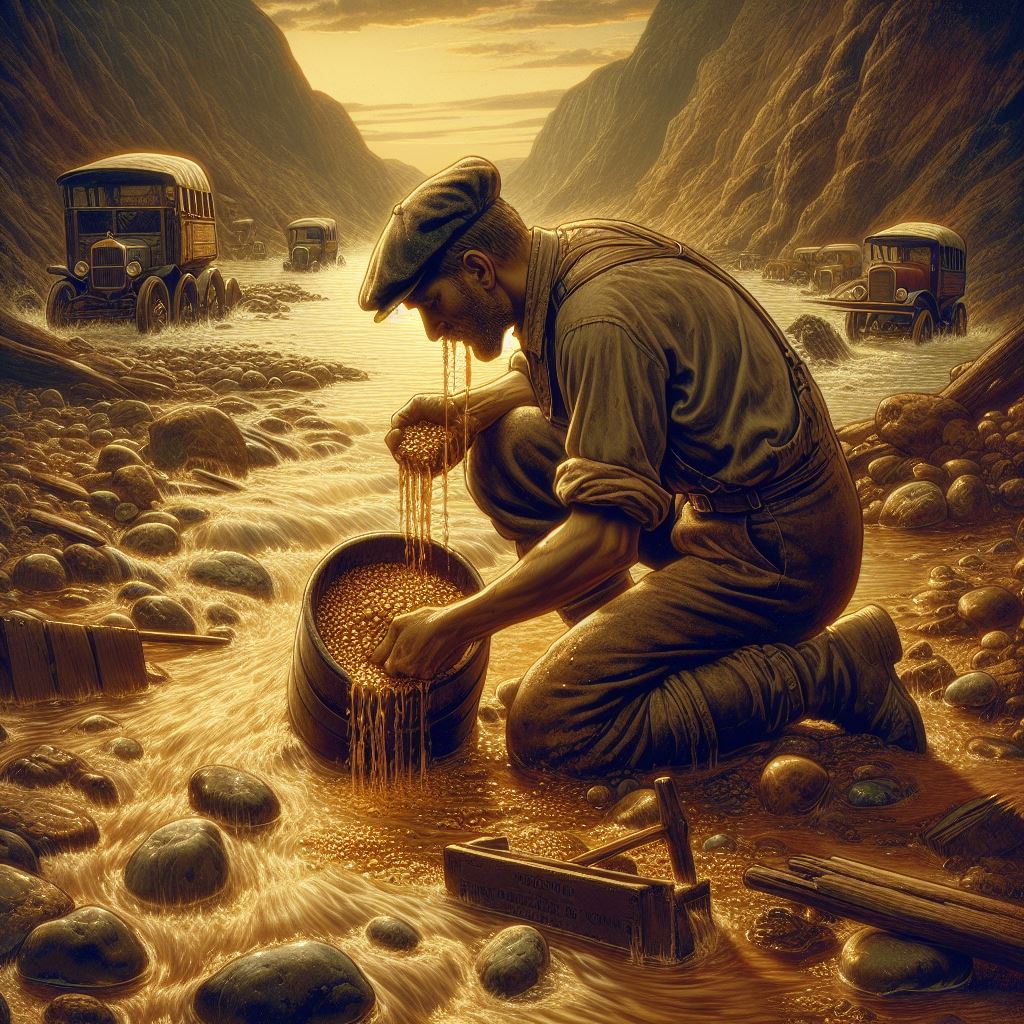

- Take the Feedback River of Feedback approach – dip your toes in as often as your curiosity allows

- Don’t treat this feedback as the final word, but breadcrumbs to discovering real, underlying (often radically different) problems

- Schedule regular blocks of time to reach out to one of the most recent input’s customers (do it soon after, so they still have a shot of remembering the original context that spurred the Feature Request, and won’t just parrot the words because they forgot why it mattered in the first place)

- Spend enough time curating the feedback items so that *you* can remember how to find it again (memorable keywords as labels, bucket as high in the hierarchy as possible), and stop worrying about whether anyone else will completely follow your classification logic.

- Treat this like the messy black box it inevitably is, and don’t try to wire it into every other system. “Fully integrated” is a cute idea – integration APIs, customer-facing progress labels, pretty pictures – but just creates so much “initialisation” friction such that every time you want to satisfy your curiosity on what’s new, it means an hour or three of labour to perfectly “metadata-ise” every crumb of feedback.

NECESSARY EMPHASIS: every piece of customer input is absolutely a gift – they took time they didn’t need to spend, letting the vendor know the vendor’s stuff isn’t perfect for their needs. AND every piece of feedback is like a game of telephone – warped and mangled in layers of translation that you need to go back to the source to validate.

Never rely on Written Feature Requests as the main input to your sprints. Set expectations accordingly. And don’t forget the 97% of all tickets must be rejected Rule coined by Rich Mironov

**Aside: what the hell do you mean that “Feature Request” is misnamed, Mike?

Premise: customers want us to solve their problems, make them productive, understood and happy.

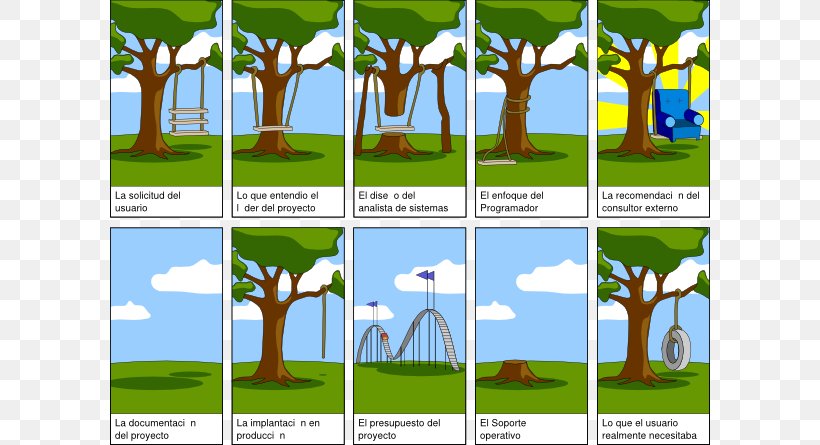

Problem: we have little to no context for where the problem exists, what the user is going to do with the outcome of your product, and why they’re not seeking a solution elsewhere.

Many customers (a) think they’re smarty pants, (b) hate the dumb uncooperative vendor and (c) are too impatient to walk through the backstory.

So they (a) work through their mental model of our platform to figure out how to “fix” it, (b) don’t trust that we’ll agree with the problem and (c) have way more time to prep than we have to get on the Zoom with them.

And they come up with a solution and spend the entire time pitching us on why theirs is the best solution that every other customers needs critically. Which we encourage by talking about these as Feature Requests (not “Problem Ethnographic Study”) – and which they then expect since they’ve put in their order at the Customer Success counter, they then expect that this is *going* to be coming out of the kitchen anytime (and is frankly overdue by the time they check back). Which completely contradicts Mironov’s “95% still go into the later/never pile“.